Audio Recording: Reading of Algonquin Legends of South Haven by Simon Pokagon (1901)

Summary:

Narrated by Corinne KasperDescription:

This recording was made possible by funding from the Less Commonly Taught and Indigenous Languages Partnership, funded by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, housed in the Center for Language Teaching Advancement (CeLTA) at Michigan State University. Recordings were done in the summer of 2022. PI for this grant project was Blaire Morseau. Translations and updated spellings for Potawatomi words were provided by Kyle Malott.

People:

Simon PokagonTranscription:

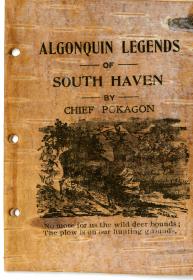

Algonquin Legends of South Haven

By

Chief Pokagon

Narrator by Corinne Kasper

No more for us the wild deer bounds; The plow is on our hunting grounds.

Our traditional account of South Haven given us by gosnanêk (our forefathers) was held as sacred by them as holy writ by white men.

Long, long pong (years) ago Ktthė mnedo (the great spirit) who held dominion over Mshigmé (Lake Michigan) and the surrounding country, selected Haw-waw-naw, a place at the wzagi (mouth) of Mkedé zibé (Black River) as his seat of government. His royal throne “Ktthė wik” was located on the highest point of that neck of land lying between Mkedé River and Lake Michigan. This high point of land was called Ish-pem-ing, meaning a high place. Here it was that Ktthė mnedo worked out the great conceptions of thibé (his soul). With giant strides he scattered broadcast along the shore, a days journey northward, multitudes of beautiful stones of various color, shape and size, that in sunshine outshone Thibékan (the galaxy on High).

No such charming stones, excepting those, could anywhere be found around all the shores of the great lake.

He also planted in mtegwagké (the forests) along the shore the most beautiful woodland flowers that ever bloomed on Earth; and filled all the trees with birds that sang the sweetest songs that ever fell on mortal ears. He also made a great mtegwap (bow) at least two arrow flights in length, and placed it along the shore. He then painted it from end to end in beautiful lines, in various hues, that outshone the countless stones he had scattered along the beach. While thus at work a cyclone from the

setting sun swept across the great lake! Wawasmowen (lightning) flashed across Wawkwik (the Heavens)! Nemki (thunder) in concert with tëgowen (the roaring waves) rolled their awful burden on the land! The Earth shook! Hail and rain beat against Him! But in His majesty, He stood smiling in the teeth of the storm!

At length the dark clouds rolled away and the setting sun lit up the passing gloom! He then picked up the giant bow that he had made, bent it across wkat (his knee), then with his breath he blew a blast that swept it eastward, between the sunshine and the clouds. As there it stood resting either end upon the trees, painting them all aglow, which in contrast with their robes of green added still more glory to the scene.

As He gazed upon its beauty and grandeur arching the departing storm, He shouted in triumph above the roaring waves in thunder tones, saying, “Kaw-ka-naw in-in-i nash-ke nin wab sa aw-ni-quod (All men behold my bow in the cloud).i See, it has no wip, sëbap, anaké bithkwan (arrow, string or quiver). It is the bow of peace. Tell it to your children’s children, that Ktthė mnedo made it and placed it there that generations yet unborn, when they behold it, may tell their children that Ktthė mnedo placed his bow in the clouds without arrow, string or quiver, that they might know He loved peace and hated war.”

The tradition above given was handed down to us by a tribe of Neshnabék (Indians) that lived in Michigan before my people, the Potawatomi. They were called Mshkodéniyêk (Prairie tribe) on account of their clearing up large tracts of land and living somewhat as farmers. They were said to be very peaceable, seldom going on the war path. The Odawas, who have always been very friendly with our people, tell us, they drove them out of this country and nearly exterminated them, about four hundred years ago.

We had much reverence for their traditions as we occupied the land of their principal odan (village) lying between Mkedé zibé (Black River) and Lake Michigan. We named it Nik-o-nong, which was derived from two Algonquin words bgeshëm (sunset) and mnowabmenagwet (beautiful). It was a lovely, as well as an important place. Ki-tchi Mi-kan, the great trail over which for ages all the northern and western tribes went around Lake Michigan to and from the great Prairies of the West, passed near this place. Traces of that great highway may still be seen along that grand sweep of country near the Lake between the Black and Kalamazoo rivers.

In the dense forest north, south and east of us were great numbers of deer, elk and bears, while duck, geese and swan clouded our waters that were swarming with fish. One half-hour’s walk north of our village was a sacred camping ground where we celebrated Thibékankéwen (our yearly six days feasts for the dead).

During this feast bon-fires were built along the shore, casting a lurid light far out into the lake and painting the crested waves all aflame. Children, young men and maidens, fathers and mothers went about the camp, feasting and saluting one another and throwing food into the fire, and as it was being consumed, would sing, “Ne-baw-baw tche baw win (we are going about as spirits feeding the dead).”ii This feast kept alive the memory of the dead as do the stones that rise above the white man’s tomb.

Nik-o-nong in its day was quite a manufacturing Indian village. Large quantities of birch bark was brought there by canoe loads and, as it never decays, was buried in the earth for use or trade when called for. Out of this wonderful bark we made canoes, hats, caps, and dishes for domestic use and our maidens tied with it the knot that sealed the marriage vow. Zisbakwet (maple sugar) was also made and kept in large quantities in this place and sold to southern and western tribes for wampum or in exchange for bzhêkéwéygen (buffalo robes).

South Haven of the white man, with all its shipping docks and cottage crowned hills, does not in beauty compare with Nik-o-nong of the red man with its deep wild woods, its bark canoes and wagwamed shores.

Here we lived for many generations in the lap of ease and plenty; but after the advent of the white man, Nature frowned upon us. Our forests were cut down; the game became scarce and kept beyond the arrow’s reach: gigo (the fish) hid themselves in deep water; the woodland birds no more cheered us with their songs; the wild flowers bloomed no more. And now all, all has changed except the Sun, Moon and Stars; they have not, because their God and Ktthė mnedo, our God, hung them beyond the white man’s reach.

Pokagon does not wish to complain. Still in wdé’ (his heart) there lingers yet a love for Nik-o-nong, the odan of his fathers. And now in old age, as with feeble step and slow he is passing through the open door of his wigwam into wawkwik (the world beyond) he must sing in his mother tongue his last song on Earth, “Nik-o-nong Nik-o-nong, nin-in-en-dam mi-notch-sa bi-naw ki-kaw-kaw-ka-naw ki-ke-tchi-twan-in nin-sa-gia Nik-o-nong (Nik-o-nong! Nik-o-nong! I shall yet behold thee in all thy glory, my loved Nik-o-nong).”iii

i The language use is very extremely broken here, it does not flow or make sense grammatically.

ii The language use is very extremely broken here, it does not flow or make sense grammatically.

iii The language use is very extremely broken here, it does not flow or make sense grammatically.

By

Chief Pokagon

Narrator by Corinne Kasper

No more for us the wild deer bounds; The plow is on our hunting grounds.

Our traditional account of South Haven given us by gosnanêk (our forefathers) was held as sacred by them as holy writ by white men.

Long, long pong (years) ago Ktthė mnedo (the great spirit) who held dominion over Mshigmé (Lake Michigan) and the surrounding country, selected Haw-waw-naw, a place at the wzagi (mouth) of Mkedé zibé (Black River) as his seat of government. His royal throne “Ktthė wik” was located on the highest point of that neck of land lying between Mkedé River and Lake Michigan. This high point of land was called Ish-pem-ing, meaning a high place. Here it was that Ktthė mnedo worked out the great conceptions of thibé (his soul). With giant strides he scattered broadcast along the shore, a days journey northward, multitudes of beautiful stones of various color, shape and size, that in sunshine outshone Thibékan (the galaxy on High).

No such charming stones, excepting those, could anywhere be found around all the shores of the great lake.

He also planted in mtegwagké (the forests) along the shore the most beautiful woodland flowers that ever bloomed on Earth; and filled all the trees with birds that sang the sweetest songs that ever fell on mortal ears. He also made a great mtegwap (bow) at least two arrow flights in length, and placed it along the shore. He then painted it from end to end in beautiful lines, in various hues, that outshone the countless stones he had scattered along the beach. While thus at work a cyclone from the

setting sun swept across the great lake! Wawasmowen (lightning) flashed across Wawkwik (the Heavens)! Nemki (thunder) in concert with tëgowen (the roaring waves) rolled their awful burden on the land! The Earth shook! Hail and rain beat against Him! But in His majesty, He stood smiling in the teeth of the storm!

At length the dark clouds rolled away and the setting sun lit up the passing gloom! He then picked up the giant bow that he had made, bent it across wkat (his knee), then with his breath he blew a blast that swept it eastward, between the sunshine and the clouds. As there it stood resting either end upon the trees, painting them all aglow, which in contrast with their robes of green added still more glory to the scene.

As He gazed upon its beauty and grandeur arching the departing storm, He shouted in triumph above the roaring waves in thunder tones, saying, “Kaw-ka-naw in-in-i nash-ke nin wab sa aw-ni-quod (All men behold my bow in the cloud).i See, it has no wip, sëbap, anaké bithkwan (arrow, string or quiver). It is the bow of peace. Tell it to your children’s children, that Ktthė mnedo made it and placed it there that generations yet unborn, when they behold it, may tell their children that Ktthė mnedo placed his bow in the clouds without arrow, string or quiver, that they might know He loved peace and hated war.”

The tradition above given was handed down to us by a tribe of Neshnabék (Indians) that lived in Michigan before my people, the Potawatomi. They were called Mshkodéniyêk (Prairie tribe) on account of their clearing up large tracts of land and living somewhat as farmers. They were said to be very peaceable, seldom going on the war path. The Odawas, who have always been very friendly with our people, tell us, they drove them out of this country and nearly exterminated them, about four hundred years ago.

We had much reverence for their traditions as we occupied the land of their principal odan (village) lying between Mkedé zibé (Black River) and Lake Michigan. We named it Nik-o-nong, which was derived from two Algonquin words bgeshëm (sunset) and mnowabmenagwet (beautiful). It was a lovely, as well as an important place. Ki-tchi Mi-kan, the great trail over which for ages all the northern and western tribes went around Lake Michigan to and from the great Prairies of the West, passed near this place. Traces of that great highway may still be seen along that grand sweep of country near the Lake between the Black and Kalamazoo rivers.

In the dense forest north, south and east of us were great numbers of deer, elk and bears, while duck, geese and swan clouded our waters that were swarming with fish. One half-hour’s walk north of our village was a sacred camping ground where we celebrated Thibékankéwen (our yearly six days feasts for the dead).

During this feast bon-fires were built along the shore, casting a lurid light far out into the lake and painting the crested waves all aflame. Children, young men and maidens, fathers and mothers went about the camp, feasting and saluting one another and throwing food into the fire, and as it was being consumed, would sing, “Ne-baw-baw tche baw win (we are going about as spirits feeding the dead).”ii This feast kept alive the memory of the dead as do the stones that rise above the white man’s tomb.

Nik-o-nong in its day was quite a manufacturing Indian village. Large quantities of birch bark was brought there by canoe loads and, as it never decays, was buried in the earth for use or trade when called for. Out of this wonderful bark we made canoes, hats, caps, and dishes for domestic use and our maidens tied with it the knot that sealed the marriage vow. Zisbakwet (maple sugar) was also made and kept in large quantities in this place and sold to southern and western tribes for wampum or in exchange for bzhêkéwéygen (buffalo robes).

South Haven of the white man, with all its shipping docks and cottage crowned hills, does not in beauty compare with Nik-o-nong of the red man with its deep wild woods, its bark canoes and wagwamed shores.

Here we lived for many generations in the lap of ease and plenty; but after the advent of the white man, Nature frowned upon us. Our forests were cut down; the game became scarce and kept beyond the arrow’s reach: gigo (the fish) hid themselves in deep water; the woodland birds no more cheered us with their songs; the wild flowers bloomed no more. And now all, all has changed except the Sun, Moon and Stars; they have not, because their God and Ktthė mnedo, our God, hung them beyond the white man’s reach.

Pokagon does not wish to complain. Still in wdé’ (his heart) there lingers yet a love for Nik-o-nong, the odan of his fathers. And now in old age, as with feeble step and slow he is passing through the open door of his wigwam into wawkwik (the world beyond) he must sing in his mother tongue his last song on Earth, “Nik-o-nong Nik-o-nong, nin-in-en-dam mi-notch-sa bi-naw ki-kaw-kaw-ka-naw ki-ke-tchi-twan-in nin-sa-gia Nik-o-nong (Nik-o-nong! Nik-o-nong! I shall yet behold thee in all thy glory, my loved Nik-o-nong).”iii

i The language use is very extremely broken here, it does not flow or make sense grammatically.

ii The language use is very extremely broken here, it does not flow or make sense grammatically.

iii The language use is very extremely broken here, it does not flow or make sense grammatically.

Location:

To navigate, press the arrow keys.

Related Items:

Digital Heritage

Community

Pokagon Band of Potawatomi IndiansCategory

Documents, ObjectsSummary

*Open PDF file to see all document pages; Birch bark book written by Simon PokagonRelated Dictionary Words:

Audio Player

Community:

Category:

Collections:

Original Date:

1901Original Date Description:

The birch bark book was published in 1901. The recording was created in 2022 and edited in 2023.Type:

Format: