Audio Recording: Reading of Algonquian Legends of Paw Paw Lake by Simon Pokagon (1901)

Summary:

Narrated by Serrina MalottDescription:

This recording was made possible by funding from the Less Commonly Taught and Indigenous Languages Partnership, funded by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, housed in the Center for Language Teaching Advancement (CeLTA) at Michigan State University. Recordings were done in the summer of 2022. PI for this grant project was Blaire Morseau. Translations and updated spellings for Potawatomi words were provided by Kyle Malott.

People:

Simon PokagonTranscription:

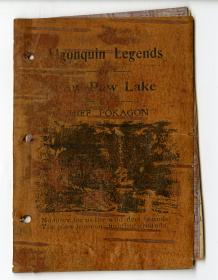

Algonquin Legends of Paw Paw Lake

By

Chief Pokagon

Narrator by Serrina Malott

No more for us the wild deer bounds;

The plow is on our hunting grounds.

Many, many ėgi ngotwak pongëk (hundred years ago) tradition as sacred to us as Holy Writ to the white man, tells us that Paw Paw Lake was a bay at the extreme western limit of zagen (a great inland lake) called by ancient Neshnabék (the Indians) Ktthė gtegan meaning an earthly Paradise. This great lake filled the valley of the Paw Paw river a canoe day’s journey towards the rising sun; and further they tell us it extended from the foot hills just south of the present site of Hartford village to the foot hills just north of where Bangor village is now located. At that time Nagneshkëmbes (Rush lake) and Wabzhi mbes (Swan lake) now called Van Auken lake, were bays connected with this large body of water on the north. One of the largest Odanwan (Indian villages) then known was built around this bay on the side towards the setting sun. This village was called Wawkwik (Heaven), a happy hunting ground. Near by it was gbéshénak (a tribal camping ground). The great mikan (trail) of all the northern and western tribes passed this place to and from mshkodé (the great prairie) beyond Lake Michigan. It was indeed an important place. Mzhéwé (elk), bzhêké (buffalo), mko (bear) and seksi (deer) in their autumn and spring migrations, either north or south, passed around the western limit of this great body of water; while unnumbered millions of mimiyêk (wild pigeons) in early spring time filled all the trees in the big forest with their nests, extending west to Lake Michigan and northward sometimes beyond Mkedé zibé (Black river). This wonderful lake swarmed with gigo (fish) and zhishib, nkëg, and wabzhi (ducks, geese and swan) floated in clouds upon its waters. In fact this ancient tribe lived in such luxury and ease that the chase was abandoned, for they could procure all bnéshi, wëyas, and gigo (fowl, flesh and fish) they wanted to eat in bimodan (near bow shot) of their wigwams. While this favored tribe was living in the lap of ease and luxury, one night in early spring, they were aroused from their slumbers at midnight by a strange roaring sound, such as they had never heard before. At first, they thought it might be Nemki (thunder) but as no wawasmowen (lightning) flashed across the sky they concluded it must be an on-coming wawyaten (cyclone), yet that did not seem

possible as not an ankwet (a cloud) was anywhere to be seen. Finally they started in the direction of the strange roaring sound, men, women and children, followed by a multitude of nëmoshêk (dogs) whining and cringing as they had never done before. Moving cautiously southward they finally reached the headlands north of where the village of Watervliet now stands, and gazing into the valley beneath, they saw by the feeble light of the moon that the shore at the outlet of their beautiful lake which for ages had held it fast, had given way and a deluge of water, roaring like a whirlwind, was sweeping down great trees and rocks towards Lake Michigan. When morning came they beheld where zagen lay when the sun went down, like an infant sleeping in its mother’s arms, a dark roily stream which appeared like some monstrous snake pushing its way through slime and mud, boiling on either side with struggling fish. Turning from the revolting sight with saddened hearts, they returned to their village. Here they found to their surprise the bay had receded a bow’s shot from their canoes, that lay the night before in circles around the shore, and their beautiful kwikwiyak (bay) was changed into a lake as it now appears. Coming to a more recent date, when our tribe the Potawatomis took possession of southern Michigan, it may be interesting to know that we called Paw Paw Lake Zaginagwna, meaning “It swallows the river in storm and spews it out in sunshine.” This name was given because in wet weather the river runs into the outlet of the lake and in a dry time it runs out at the same place into the river again. Hence the name from the Algonquin words meaning swallow and vomit. Indians in naming their children always give some reason for the name, and in naming places the same custom is adhered to. Pokagon does not wish to complain of the white man, yet must admit he longs, in his heart, again to behold the beauty of Zaginagwna, the odena of his fathers. Here we killed the bear, the elk and the deer. Here we trapped gdedé, éspen and mëk (the otter, coon and beaver). But alas, our forests have been cut down! Our woodland flowers, for want of shade, have faded and died! Our ancient trails cannot be traced! Our fathers’ graves have been destroyed, and where our wigwams once stood and our children played now stands the cottages of the white man. All, all has changed except gizes, dbëk gizes and nëgosêk (the sun, moon and stars), and they have not because their God and Ktthė mnedo (our God) in great wisdom and mercy, hung them beyond the white man’s reach.

By

Chief Pokagon

Narrator by Serrina Malott

No more for us the wild deer bounds;

The plow is on our hunting grounds.

Many, many ėgi ngotwak pongëk (hundred years ago) tradition as sacred to us as Holy Writ to the white man, tells us that Paw Paw Lake was a bay at the extreme western limit of zagen (a great inland lake) called by ancient Neshnabék (the Indians) Ktthė gtegan meaning an earthly Paradise. This great lake filled the valley of the Paw Paw river a canoe day’s journey towards the rising sun; and further they tell us it extended from the foot hills just south of the present site of Hartford village to the foot hills just north of where Bangor village is now located. At that time Nagneshkëmbes (Rush lake) and Wabzhi mbes (Swan lake) now called Van Auken lake, were bays connected with this large body of water on the north. One of the largest Odanwan (Indian villages) then known was built around this bay on the side towards the setting sun. This village was called Wawkwik (Heaven), a happy hunting ground. Near by it was gbéshénak (a tribal camping ground). The great mikan (trail) of all the northern and western tribes passed this place to and from mshkodé (the great prairie) beyond Lake Michigan. It was indeed an important place. Mzhéwé (elk), bzhêké (buffalo), mko (bear) and seksi (deer) in their autumn and spring migrations, either north or south, passed around the western limit of this great body of water; while unnumbered millions of mimiyêk (wild pigeons) in early spring time filled all the trees in the big forest with their nests, extending west to Lake Michigan and northward sometimes beyond Mkedé zibé (Black river). This wonderful lake swarmed with gigo (fish) and zhishib, nkëg, and wabzhi (ducks, geese and swan) floated in clouds upon its waters. In fact this ancient tribe lived in such luxury and ease that the chase was abandoned, for they could procure all bnéshi, wëyas, and gigo (fowl, flesh and fish) they wanted to eat in bimodan (near bow shot) of their wigwams. While this favored tribe was living in the lap of ease and luxury, one night in early spring, they were aroused from their slumbers at midnight by a strange roaring sound, such as they had never heard before. At first, they thought it might be Nemki (thunder) but as no wawasmowen (lightning) flashed across the sky they concluded it must be an on-coming wawyaten (cyclone), yet that did not seem

possible as not an ankwet (a cloud) was anywhere to be seen. Finally they started in the direction of the strange roaring sound, men, women and children, followed by a multitude of nëmoshêk (dogs) whining and cringing as they had never done before. Moving cautiously southward they finally reached the headlands north of where the village of Watervliet now stands, and gazing into the valley beneath, they saw by the feeble light of the moon that the shore at the outlet of their beautiful lake which for ages had held it fast, had given way and a deluge of water, roaring like a whirlwind, was sweeping down great trees and rocks towards Lake Michigan. When morning came they beheld where zagen lay when the sun went down, like an infant sleeping in its mother’s arms, a dark roily stream which appeared like some monstrous snake pushing its way through slime and mud, boiling on either side with struggling fish. Turning from the revolting sight with saddened hearts, they returned to their village. Here they found to their surprise the bay had receded a bow’s shot from their canoes, that lay the night before in circles around the shore, and their beautiful kwikwiyak (bay) was changed into a lake as it now appears. Coming to a more recent date, when our tribe the Potawatomis took possession of southern Michigan, it may be interesting to know that we called Paw Paw Lake Zaginagwna, meaning “It swallows the river in storm and spews it out in sunshine.” This name was given because in wet weather the river runs into the outlet of the lake and in a dry time it runs out at the same place into the river again. Hence the name from the Algonquin words meaning swallow and vomit. Indians in naming their children always give some reason for the name, and in naming places the same custom is adhered to. Pokagon does not wish to complain of the white man, yet must admit he longs, in his heart, again to behold the beauty of Zaginagwna, the odena of his fathers. Here we killed the bear, the elk and the deer. Here we trapped gdedé, éspen and mëk (the otter, coon and beaver). But alas, our forests have been cut down! Our woodland flowers, for want of shade, have faded and died! Our ancient trails cannot be traced! Our fathers’ graves have been destroyed, and where our wigwams once stood and our children played now stands the cottages of the white man. All, all has changed except gizes, dbëk gizes and nëgosêk (the sun, moon and stars), and they have not because their God and Ktthė mnedo (our God) in great wisdom and mercy, hung them beyond the white man’s reach.

Location:

To navigate, press the arrow keys.

Related Items:

Digital Heritage

Community

Pokagon Band of Potawatomi IndiansCategory

Documents, ObjectsSummary

*Open PDF file to see all document pages; Birch bark book written by Simon PokagonRelated Dictionary Words:

Audio Player

Audio Player

Audio Player

Community:

Category:

Collections:

Original Date:

1901Original Date Description:

The birch bark book was published in 1901. The recording was created and edited in 2022.Type:

Format: